Curious as to why some people are creative?

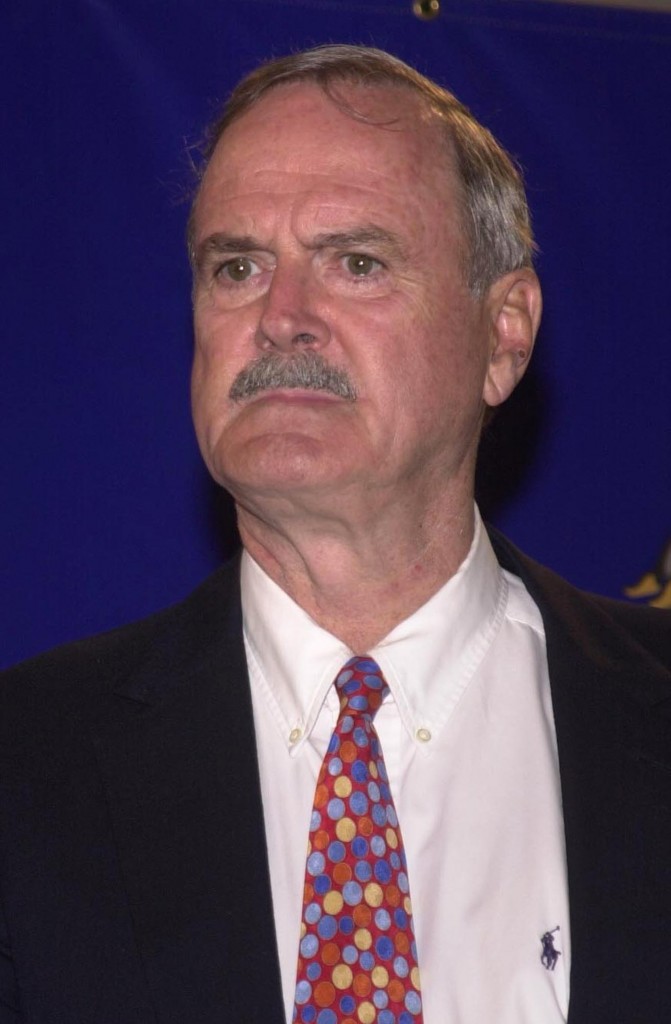

“It’s not about the talent; it’s a way of operating,” said John Cleese in his 1991 speech given on creativity to Video Arts, a UK-based e-learning company. If you haven’t seen it, it’s worth your time, not only for what Cleese says about how creative types operate but also how he cleverly and seamlessly tells you about how many you-name-its that it takes to change a light bulb.

My favorite:

Q. How many psychiatrists does it take to change a light bulb?

A. Only one, but the bulb has got to really WANT to change.)

You can view the entire video, complete with German subtitles at John Cleese On Creativity.

Cleese claims 5 things are needed in order to get into the creative mode.

They are:

1. Space

2. Time

3. Time (and no, I’m not repeating myself)

4. Confidence

5. Humor.

1. Space. Separate yourself so curiosity can operate.

Cleese says that to become creative (what he calls playful), you need to separate yourself from your everyday life and its routine. Cleese says, “Seal yourself off. Make a quiet space for yourself where you will be undisturbed … where curiosity, for its own sake, can operate.”

Cleese tells of findings, done by the University of California-Berkeley and Donald MacKinnon, and their fascinating discovery that most creative people do not have higher I.Q.s than their colleagues, but they have mastered a way to operate in a creative mode, a mode Cleese said, “which allows natural creativity to function.” One of those modes, Cleese said, is the open mode and it includes

“playing with ideas,

exploring these ideas,

not for any immediate practical purpose

but just for enjoyment.”

In the open mode, we are open to anything that comes into our consciousness. We give ourselves permission to brainstorm without critiquing.

“The open mode is relaxed, expansive, less purposeful, more contemplative, inclined to humor, which always accompanies a wider perspective and where we’re more playful,” Cleese said. “It’s a mode. . . where we’re not under pressure to get something done quickly. We can play and that is what allows our natural creativity to surface.”

Cleese believes that Alexander Fleming was in the open mode when it led him to the discovery of penicillin, for Fleming became curious as to why no culture had grown on one of his dishes. That “curiosity for its own sake,” caused Fleming to stop and observe and questioned what had happened.

The closed mode, the second operating mode of creativity, is where we pull back from our open mode, i.e., our “play” and implement our ideas. Here is where we test and examine our ideas, find ways to make them work and make decisions on them. The two parts, the open and closed modes, create creative flow as does the bouncing back and forth between these two modes. Both are equally important.

2. Time. “Play” for about 90 minutes. Much like we schedule meetings and “do lunch” with a friend, we need to schedule creative time to be in the open mode. But we need to set boundaries around that time. Cleese suggests 90 minutes rather than a longer amount of time to play. Cleese says, “It’s only by having a specific moment when your space starts and an equally specific moment when your space stops that you can seal yourself off from your everyday closed world in which we habitually operate.” He cites Johan Huizinga, an historian who studied play, who said, “Play is distinct from ordinary life, both as to locality and duration. This is its main characteristics. It’s limitedness. It’s secludedness. Otherwise, it’s not play.”

Once you’ve create that “oasis of quiet,” don’t try to dive right in. You’ve only just allowed your body a place to quiet down. Give yourself 30 minutes to let your brain declutter and get to quiet. Once it has stilled from to-do lists and the rat race, sit, ponder, put random ideas onto paper. Allow yourself a good chunk of time. Don’t put a whole morning aside for, Cleese says, “Your mind will need a break.”

3. Time. Work past the anxiety of unresolvedness. This “time” refers to the time spent sticking with the problem through the uncomfortableness of it being unresolved and not yet being something we can check off as being completed. What he means by this, is oftentimes, when we’ve been back and forth in open and closed modes of creativity, that we stop before we should. And why we stop before we get to the deep end of the pool is because we’re uncomfortable in the feelings that accompany unresolvedness. We look at the clock, see it’s closing time at the zoo and stop short of what we really could have done had we let our fingers get all pruny and fought for a more creative, brilliant outcome. Cleese tells the story of a fellow writer on Monty Python, whom Cleese thought possessed better talent than did he, but the writer took an easier way out to solve the creative problem so he could leave at the end of the working day. Cleese said that personally he could not close shop at 5 p.m. “I stuck with the problem longer,” Cleese said, past those feelings of anxiety caused by a solution not coming to him by closing time. The result? Lucky us. We are beneficiaries of his working past the state of uncomfortableness. We’ve seen his work and brilliance. Only in reading MacKinnon’s work did Cleese learn what he’d instinctively known all along, that “the most creative professionals always played with the problem for much longer before they tried to resolve it, because they were prepared to tolerate the slight discomfort, feelings and anxieties that come when we haven’t solved a problem.” Those like Cleese, “put in more pondering time; their solutions thus, are more creative.” And while Cleese is adamant that professionals meet deadlines, he isn’t afraid to say, “Look, baby cakes. I don’t have to decide until Tuesday and I’m not chickening out of my creative discomfort by making a snap decision before then. That’s too easy.”

“Give yourself time to come up with something that is original.”

What Cleese is saying to me is this: In your creative mode, be willing to get comfortable in uncomfortableness and something amazing will happen.

4. Confidence. True play involves saying and writing things that are nonsensical but, given time, will lead to breakthroughs.

Nothing will stop your being creative than the fear of making a mistake, Cleese said, for when you think about play, “True play is experiment.” “You’ve got to risk saying things that are silly and illogical and wrong,” he tells his audience, “and the best way to get the confidence to do that while you’re being creative is to know that nothing is wrong. There’s no such thing as a mistake and any drivel may lead to the breakthrough.”

Be confident as you create or play, knowing it is time well spent on your project. When you were a child, what sorts of ways did you engage in creative play?

I remember my sons playing “guys” in the neighbor’s sandbox. One minute they had built a castle for their toy figurines, the next a fort, the next, they flooded the sandbox, the next they had moved their army to the tree house. They were “at play.” Translate what you surrounded yourself with when you played as a child to current time. Explore with an “anything goes” mentality. Bring what you’ll need, too. My “play” time consists of mind maps, colored pencils, drawing objects, an old dictionary, and random images (to find possible connections between them). The point, in creative play is to, in confidence, be expansive in thought.

Cleese puts it this way. “If there is any essence of playfulness, it is an openness to anything may happen. The feeling that whatever happens is ok. So you cannot be playful if you’re fearful that moving in some direction could be wrong. Something you shouldn’t have done. You’re either free to play or you’re not. As Alan Watts puts it, ‘You can’t be spontaneous within reason.’”

5. Humor makes us playful, enter creative mode faster, and gets us gems like unladen swallows.

“Humor is an essential part of spontaneity and an essential part of playfulness and an essential part of the creativity that we need to solve problems, no matter how serious they may be,” Cleese said. Comic relief lightens our day. Cleese believes humor gets us into the open mode faster than anything else can. “Laughter brings relaxation. Humor makes us playful,” he said. Humor is much like creativity, says Cleese, in that “in a joke, the laugh comes at a moment when you connect two different frameworks of reference in a new way. And isn’t that what we do when we’re being creative? We’re questioning. We’re asking, ‘What if I do this?’ ‘What if we do that?’ and looking for curious ways to connect the two.”

“[H]having a new idea is … connecting two hitherto separate ideas in a way that generates new meaning. Now, connecting two different ideas isn’t difficult. You can connect cheese with motorcycles or … bananas with international cooperation. You can get any computer to make random connections, but these new connections or juxtapositions are significant only if they generate new meaning,” Cleese said. “So as you play, you can deliberately try connecting these random juxtapositions and then use your intuition to tell you whether any of them seem to have significance for you. That’s the bit between you and the computer. It can make any kind of connections, but it’s up to you to determine whether any of them smells interesting. And of course, you’ll produce some juxtapositions that are absolutely ridiculous, absurd.”

In Monty Python and the Holy Grail, (click here to view it on Youtube) Cleese and his fellow writers found ways to do this as in this outtake:

1st soldier with a keen interest in birds: Are you suggesting coconuts migrate?

And in the classic scene at the Bridge of Death:

Bridgekeeper: Stop. Who would cross the Bridge of Death must answer me these three questions three, ere the other side he see.

Sir Lancelot: Ask me the questions, bridgekeeper. I am not afraid.

Bridgekeeper: What…is your name?

Sir Lancelot: My name is Sir Lancelot of Camelot.

Bridgekeeper: What is your quest?

Sir Lancelot: To seek the Holy Grail.

Bridgekeeper: What is your favorite color?

Sir Lancelot: Blue

Bridgekeeper: Go on. Off you go.

Sir Lancelot: Oh, thank you. Thank you very much.

Sir Robin: That’s easy.

Bridgekeeper: Stop. Who would cross the Bridge of Death must answer me these three questions three, ere the other side he see.

Sir Robin: Ask me the questions, bridgekeeper. I’m not afraid.

Bridgekeeper: What is your name?

Sir Robin: Sir Robin of Camelot.

Bridgekeeper: What is your quest?

Sir Robin: To see the Holy Grail.

Bridgekeeper: What is the capital of Assyria?

(pause)

Sir Robin: I don’t know that.

(he is thrown over the edge of the volcano)

Sir Robin: Awwwwwwwgh.

Bridgekeeper: Stop. What is your name?

Galahad: Sir Galahad of Camelot.

Bridgekeeper: What is your quest?

Galahad: I seek the Grail.

Bridgekeeper: What is your favorite color?

Galahad: Blue. No, yell..

(he is also thrown over the edge)

Galahad: awwwwwwgh.

Bridgekeeper: Hee hee heh. What is your name?

King Arthur: It is “Arthur,” King of the Britons.

Bridgekeeper: What is your quest.

King Arthur: To seek the Holy Grail.

Bridgekeeper: What is the air-speed velocity of an unladen swallow?

King Arthur: What do you mean? An African or European swallow?

Bridgekeeper: Huh? I…I don’t know that.

(he is thrown over)

Bridgekeeper: Awwwwwwwwgh

Sir Bedevere: How do you know so much about swallows?

King Arthur: Well, you have to know these things when you’re a king, you know.

Listening to Cleese will take some time. Listen in the car, as you work-out or walk the dog. His takeaways and well-thought-out speech is worth a listen. And, a bonus is that you’ll get to hear Cleese’s brilliant timing, the way and how he weaves in his slew of light bulb jokes. If you’d like a pdf of Cleese’s speech, you can find it by clicking the link below.

About Julie Saffrin

Julie Saffrin is the author of numerous published articles and essays. Her latest book, BlessBack: Thank Those Who Shaped Your Life, explores the power of gratitude and offers 120 creative ways to journey toward positive, lasting change.

Love this post, Julie! Will be listening! 🙂

Thanks, Joy. Hope you enjoy the message as much as I did.