Black and white picture: Harry Driste receiving a plaque and being presented with a tree planted in his honor at his retirement as janitor at River Ridge Elementary School in Bloomington, Minnesota.

You are here to enrich the world, and you impoverish yourself if you forget the errand.

— Woodrow Wilson

Every once in a while someone comes along and changes your life. Harry Driste was one of those people. Harry passed away on June 3, 2012 at the age of 101 1/2. Until two days before his death, Harry was alert, making jokes and reaching into his storehouse of tales, including having served and fed Al Capone in his Chicago restaurant and remembering fondly the day that River Ridge Elementary School in Bloomington, Minn., planted a tree in his honor and filled a toilet with money for him to enjoy in his retirement. He will be greatly missed by me, my brother Steve Trewartha and my mom Carol Trewartha, the 88th Street Pussycats, (read the story below), his family – including my sister-in-law Jenny Driste Lee who was his granddaughter and who is married to my brother, Mark Trewartha – who Harry loved as if he were his own grandfather. Harry is survived by his children, including Jenny’s dad, Bob Driste (wife Karen), and many other family members, as well as his older sister who just turned 105. Harry’s funeral will be Thursday, June 7 in Paynesville at 11 a.m. To read his obituary or leave a note on the family’s guestbook, please click here. The family prefers memorials in lieu of flowers. I’m thinking I need to find a place in the world where we can donate some erasers. If you have an idea, post it in the comment section of this post. I think Harry would love knowing, even in death, he’s giving someone a BlessBack.

Ironically this Thursday, June 7, the Bloomington Sun-Current will feature BlessBack and my story about Harry’s unique connection to my family. I will post the story on Thursday, but for now, below is the story featured in BlessBack. It has been my honor to know this wonderful man.

Julie

Eraser Man – Harry Driste

My two brothers, Mark and Steve Trewartha, and I went to an elementary school three blocks from our house in Bloomington, Minnesota. Our best memory is when our teachers asked us to clean the chalkboard erasers. As a kid, cleaning erasers at River Ridge Elementary School meant escape from class at the time of day when you ached for the school bell to ring. No one in authority questioned your presence in the empty halls at ten minutes to three because they saw you carrying erasers like logs to a campfire.

Our school was round and classrooms had doorless, wide entries so when you walked by, students looked at you with eraser-envy. One smirk was enough to rub it in that your day was done. Another twenty paces took you past the lunchroom where Miss Stella counted lunch tickets and the day’s earnings, past the nurse’s office and who was in trouble in Principal Tufino’s office. Finally you reached that hallowed, mysterious place that housed the cleaning machines — the custodian’s office.

Our custodian Mr. Driste, or “Harry,” as he preferred, reminded me of a mix between a tall, happy Mr. Magoo and G.I. Joe. He had a shiny head, was trim, and wore wire-rimmed glasses, grey shirt and pants, and heavy boots that propelled his long stride. A keyring clipped to his belt loop had a wire zipline that seemed to stretch the gym’s width.

Harry could have cleaned the erasers himself; instead he remembered he was once a kid at the end of a school day and figured out a way for students to escape. For the kids, it was heaven; for Harry, it was a chance to show kids his working world — one in which he was immensely proud.

Unlike teachers and their private lounge, Harry welcomed us into his world. Once inside Harry’s “office,” on the side of the gym, you not only felt safe because it was near the bomb shelter, but you felt secure because Harry was there and Harry could do anything. In his soft-spoken manner, he showed children how to clean erasers, both the black-felt version and the longer chamois-and-rubber ones.

His office smelled like soap, chemicals and wax; it held tools and equipment that intrigued. He used different cleaning products than Mom used. There was no Mr. Clean, Janitor in a Drum, or Big Wally on his shelves but industrial-looking cans with images of pirate flags and scary letters that reminded me of the Soviet Union. His brooms looked different, too. They were short-bristled and wide. Two damp spaghetti mops hung in a neat row next to a floor drain. He had a galvanized aluminum mop bucket on wheels with a built-in squeegee lever.

Cleaning erasers took only two minutes — never long enough. We just didn’t want to leave Harry’s office. Students loved Harry. I loved him because of the pride he took in caring for the school gymnasium floor. Every week he buffed it to squeaky perfection. He also learned all four hundred of our names, no small feat at seventy-three. He wanted to know us. He illuminated us, made us feel visible.

For some, Harry was a surrogate parent. For kids whose parents didn’t come to band concerts, Harry stayed late, leaned against his office door in the gymnasium, and sipped coffee from the cup of his Thermos, smiling approval at our grunts and squeaks.

As kids do, we moved on to junior high. In ninth grade, we learned Harry planned to retire at the end of the school year. A handful of kids from my neighborhood made a giant card. We drew a fish with big scales, signed our good lucks, and gave it to him. He was blurry-eyed as he thanked us.

We graduated high school. Our elementary school closed due to low enrollment. A corporation bought the building. We went to college, got jobs, married and had kids.

Life advanced the years. Twenty-five, in fact.

My brother Mark fell in love with Jenny in 1998. They went to visit Jenny’s grandfather and his wife at their home a couple hours west of the Twin Cities.

Jenny’s grandpa introduced himself to Mark as Harry Driste.

Flabbergasted, Mark told him about being a student at River Ridge and asked if he had worked there.

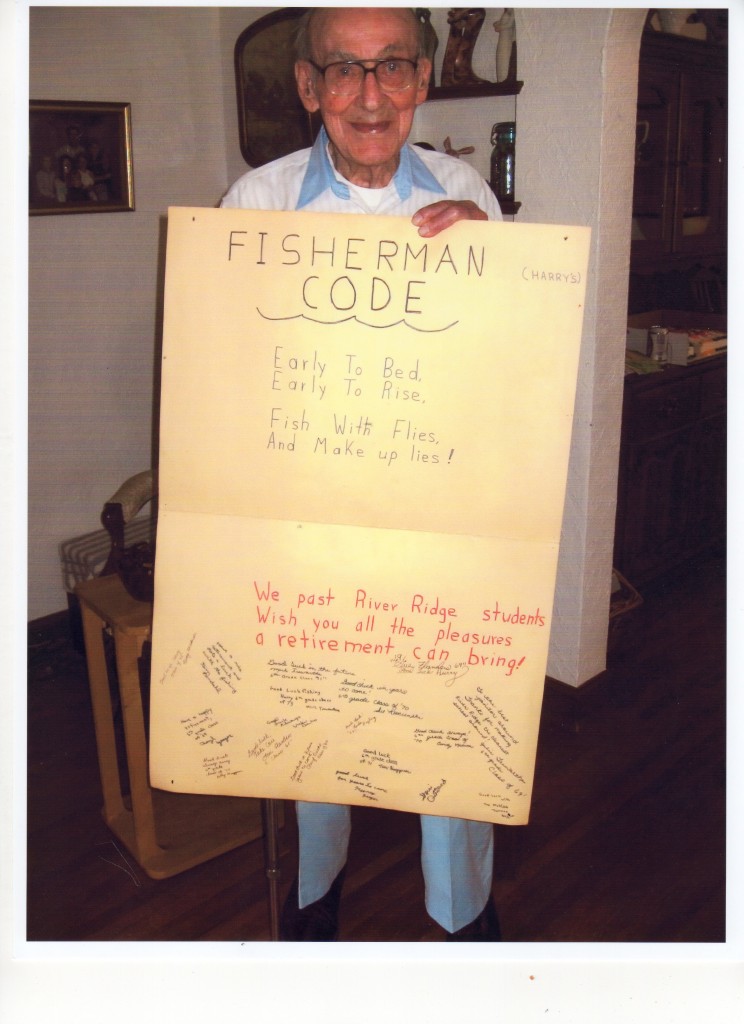

Harry didn’t answer. Instead, he said he wanted to show Mark something in his finished basement. Mark followed Harry. Hanging on the center of a paneled wall was a two- by three-foot manila-colored poster with a giant fish drawn on it. “Harry’s Fisherman Code: Early to bed, early to rise. Fish with flies, and make up lies!” was on the top half. On the bottom half, in colored pencils and magic markers, were written our childhood farewells.

Mark called later that evening. “You won’t believe it,” he said and told me the story.

Mark and Jenny married. Years later, Jenny’s daughter, Emma, graduated in 2007 from high school and Jenny’s parents drove to Paynesville to bring Harry, then ninety-seven, and his wife to the graduation open house in Minneapolis.

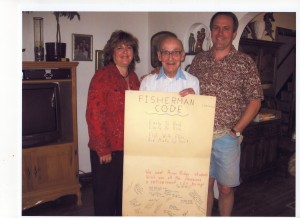

When I entered Mark’s house, Harry was in an arm chair and he’d brought the retirement poster from twenty-five years ago and held it up to show me. He still had the same smile.

We hugged and talked about River Ridge. “That was the best place I ever worked,” he said. “You kids always treated me so nice.”

He opened the big card. I saw my handwriting tucked in a corner. “To the best janitor around,” it said. “Thanks for making River Ridge the cleanest school in town.” I looked at the circle of signatures — some of whom were still my best friends. My brothers had signed it, as had neighbor kids who had moved, and another, Vicki Davis, who had died at eighteen. All of us, just teens at the time, had left our thanks and wishes for his happiness in retirement.

Our simply constructed send-off held such meaning for Harry; it was a visible affirmation in his retirement that he had lived a meaningful life. It told him that his presence at school had a positive impact on the students and we, in turn, had illuminated him.

I am still friends with a handful of my elementary school friends. In fact, we’ve known each other since I was four. Sue Koscienski, Cheryl Yeager, Sherry Dircks, Cindy Nelson, and I have learned much from one another through the years. As young children, we practiced our weddings with Bridal Doll Box paper dolls. As teens, they counseled me when my heartthrob, Bobby Sherman, who’d asked in a song if I loved him, married someone else. We weathered the drama of high school together. We celebrated our marriages, our children’s births and their graduations, and we’ve sat by each other’s sides as we’ve said loving good-byes to those we’ve lost. Early on, Cindy named us the 88th Street Pussycats. We meet every six weeks for dinner. It’s been that way for more than thirty years.

At a recent dinner with the 88th Street Pussycats, I shared pictures taken of Harry at the graduation party, and the card we had made him. “You know,” Cindy said, “seeing that card makes me realize that we were good kids back then and that we thought of someone other than ourselves.”

Receiving thanks from Harry twenty-five years later for something we had forgotten we’d done was a true surprise. Reconnecting with a man who was a hero to us because he treated us kindly was a gift. But seeing Harry and the card again through adult eyes, a deeper meaning unveiled itself. He was a safe adult at school, a friendly presence, with no way to influence our report cards; thus he could interact and be available to us in a more relaxed way than our teachers. Given this freedom, Harry chose to build relationships with the students. His smile was an invitation to be his friend.

When people with good intentions sincerely welcome you into their world, they are giving you access to the way in which they live life. In Harry’s case, he gave four hundred students access to his work. Harry’s office was the first time many of us had seen someone’s work environment. He built a little community of helpers who felt valued because he made us feel that cleaning erasers was an important first job. In giving of himself, Harry created a bond with us.

At the graduation party, when Harry showed us the card, he revealed again that our young presence had mattered to him.

Harry turned one hundred in the summer of 2010. A “Happy 100” card made the rounds of the old River Ridge gang to sign it, offering Harry more good wishes.

Colliding into something good from one’s past feels serendipitous, as though God pre-orchestrated a lavish delight just for us. When we encounter such a moment, we make a sweet connection between the past and present, and we receive joy.

Something else occurs, too: A BlessBack.

The River Ridge gang recognized Harry’s kindness and created a handmade retirement card that specifically said why they were thankful. They blessed him back for his kindness, for inviting them into his office, for making the school look good, for coming to their concerts and for learning their names.

Years later, other BlessBacks happened, too. First, when Harry showed Mark the oversized card, he blessed Mark back in two ways. Just revealing that he had kept the twenty-five-year-old card gave Mark a BlessBack, for Harry showed Mark how much he valued the students’ recognition. Secondly, Harry told Mark that the kids made just as big an impact on him as he had on them.

Later, when I told the 88th Street Pussycats the story, they received a BlessBack. They learned, as young people, they had unknowingly made a difference in Harry’s life, too.

When people give a BlessBack, they are letting another know how he or she impacted their life. When people receive a BlessBack, they discover that they matter and have made a difference in someone’s life. When this occurs, a beautiful exchange of blessing — an illumination — happens. BlessBacks, once in motion, are circular, and ever-expanding. The BlessBack of Harry touching our lives, of us touching his life, came around and touched us once again.

At times our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person.

Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.

— Albert Schweitzer

Copyright, 2012 by Julie Saffrin

Excerpted from BlessBack: Thank Those Who Shaped Your Life. No reprint or use of this material may be used in any capacity without the expressed written permission of the copyright holder.

To buy BlessBack: Thank Those Who Shaped Your Life, click here.

To like or to follow BlessBack’s Facebook Fan Page, click here.

To follow BlessBack on Twitter, click here.

[pinit]

About Julie Saffrin

Julie Saffrin is the author of numerous published articles and essays. Her latest book, BlessBack: Thank Those Who Shaped Your Life, explores the power of gratitude and offers 120 creative ways to journey toward positive, lasting change.

What a wonderful tribute, Julie.

Nice story Julie. Lots of great memories of River Ridge and hanging out with your brothers.

Hi Scott. So nice to hear from you. We grew up in such a great neighborhood, didn’t we? The Hoeppner family was a huge part of it.

Great piece of writing, Julie